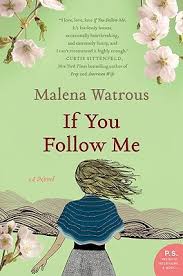

Malena's first novel, If You Follow Me, is a magnificent cross-cultural exploration of small town life in Japan based somewhat on her own experiences in that country. It's a wonderful book and she was very generous with her thoughts about writing it and about teaching writing generally.

When I asked her some searching questions, here's what she had to say...

KC: When you wrote "If You Follow Me", you were really writing for a New Adult audience before NA was even recognized as a distinct market category. What draws you to writing about characters at that stage of their lives?

MW: I think there are a number of answers to that question. One is that I'm the kind of writer who draws a lot of inspiration from my life, and I'm probably always going to be trying to understand the stage that I'm outgrowing. I began that book in my late twenties, so I was interested in exploring a character in her early twenties, done with college and on the cusp of adulthood but still fairly clueless about how to care for herself or create an independent life. Like my main character, I'd gone to Japan for a couple of years, and that experience was interesting to me because it was kind of an incubator: real life but not really. I think a lot of expats who end up staying in their expat bubbles overseas actually do so because they like this aspect of the existence: the sense that what you do or how you act doesn't exactly matter. One title I considered for the novel was "Temporary People." But I think that's part of being the "New Adult" age as well. For me at least, I kind of knew at that age that no matter how strong I felt about anyone I might have been in a relationship with, it probably wasn't going to be a lifelong relationship. Everything was temporary or transient. I think that sense that I had gave that time of life a feeling of being both exciting and (in the long term) inconsequential, like it was a sketchpad, to practice before doing the real drawing. So that's one answer. But even though I'm now further past that age (nearing 40, and the mother of a 7 year old) I think I would write about it again, and will. I think that the most interesting characters in fiction have restrictions imposed upon them that they have to buck and fight against, and young people tend to have more restrictions, because they don't have as much power yet, or as much control over their lives. They're typically on the verge of change, and they haven't quite become who they might want to be yet. All of this makes it rich and fertile ground for a novelist.

KC: You handled the cross-cultural issues in the book so beautifully, particularly the use of Japanese small town language and customs. Was it difficult to incorporate that material and make it accessible to a largely American/English-speaking audience?

MW: It was challenging but fun. To get back to that idea of fertile restrictions, that was how I felt about having so many scenes in which I had characters who couldn't really communicate easily, because one person barely spoke Japanese and the other barely spoke English. I tried really hard to make their conversations plausible within these limitations, and it was sometimes tricky, but I also enjoyed the exercise in minimalism. Like: what kind of deep emotional stuff can you get across even if you only have 50 shared words? Can you joke around with mutually limited vocabularies? Having lived in rural Japan and gone through some similar stuff to my character, I knew that the answer was yes, and the trick was to reproduce that on the page, if possible. I think I also knew that my book wouldn't appeal to everyone. There are readers who find it really off putting to encounter foreign words in a novel. But I figured those people probably wouldn't want to read about someone going to live and work in rural Japan, and if you try to please everyone, you end up pleasing no one. (Or so I consoled myself...)

KC: How did you go about researching the book? I know you spent some time in Japan. How autobiographical is it, if at all?

MW: It's highly autobiographical, but also very much a novel. I had lived in a town like the one in my novel for a year, before moving to a city. A lot of the setting details (the Alice in Shikaland nuclear power museum, for instance) are real. But the characters are made up or else hybrids of various people. Some of the emotional content was personal (isn't it always in a novel?) but the story arc was wholly invented. For "research," I read all the Japanese fiction I could, saw tons of Japanese movies, and eventually took a trip back to Japan to make sure I had the feel of the place right, but I didn't have to do much straight research because it's not historical or anything like that. Oh, I did have a Japanese friend go over all of the Japanese language to make sure that I wasn't grossly messing up anything that people were saying.

KC: As well as being a wonderful writer, you are also a writing teacher. What are some of your favorite things about teaching students to express themselves through the written word? What are some of the biggest challenges?

MW: Thank you! I have always taught as well as written. My mother is a teacher, and I grew up watching her do it as naturally as breathing, and I think it rubbed off. I started teaching writing in college and it's something I've continuously done simultaneously with my own writing. I feel like I learn how to teach writing from writing itself, and I learn how to write from teaching writing and watching my students evolve. They're connected processes for me. A challenge in both is to return to a kind of "beginner mind." I think sometimes the danger from having been at something like this for a while is to get impatient, to forget that everyone needs to learn and practice the same kind of rudimentary things, and just because I've told 9 classes of students something doesn't mean that students in the 10th class should intuit it or get it any faster. Speed is a funny thing, too. I think that with writing, you figure out how to use what you learn, how to apply craft knowledge, in your own time. Students might learn something in one class early on, but only figure out that it matters or how to apply it 2 years later. Novel writing is definitely something where patience pays off, patience and persistence, and this is true in teaching as well. One thing I learned early in my teaching career, but that continues to surprise me in its trueness, is how much I learn as a teacher if I take the time to talk to a student writer and ask him or her questions about the work. So often that person has all kinds of answers that aren't on the page and probably should be. It's almost always all there: in the text itself, in the draft, in the head of the writer. My job as a teacher, I've found, is mostly to ask the right questions to help the writer bring that material out. This is enormously rewarding but it can also be a challenge. It might seem easier, often, to impose my own vision for the work, to try and diagnose or "fix" it. But the joy in this is watching someone over the course of a term or year (or however long) learn from lectures and critiques and conversations and reading and manage to apply this new knowledge to getting a story out in a way that is more unique, vivid and true. I'm at the end of a course right now, and have watched all of the students who persisted make enormous improvements. I feel hugely proud of them, because I know that it can be hard to believe that the breakthrough will happen, but it will and it has! That is super exciting, and I don't take any kind of credit for it, but I do feel like a kind of midwife. I love what I get to do.

KC: Who are your main writing influences? What are you reading now?

MW: I've had a great run of reading lately. In "kidlit," I'm reading The One And Only Ivan to my son, and we are loving it, although it's super sad. I loved "The Paying Guests" by Sarah Waters. I'm also really enjoying Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng. I don't know that I have particular influences. I read so much for work that when I read a book for pleasure, I just pick up whatever I have heard good things about lately and give it a try, and if I don't love it then I move on. I never feel like I have to finish a book (unless it's for work) out of a sense of duty. Life's too short, and I have only so much time for pleasure reading. I am always looking for novels that are both funny and sad (my favorite combination) and usually contemporary, and I love a little mystery angle too--suspense is good. Also, I recommend another great book called Adam, by Ariel Schrag. I've seen it billed as adult and YA. Kind of like Peter Cameron's wonderful Some Day This Pain Will Be Useful To You. Adam is about a teen boy posing as an FTM transgendered person to score a girlfriend along his sister's lesbian crowd one summer in NY. It's hilarious and raunchy and so perceptive about the insecurity of that age. It was one of my favorite books of the year for sure and I want more readers to know about it!

KC: If you could give one piece of advice to a new writer, what would it be?

MW: It's always the same: Write the book that you want to read. I feel like this is one of those simple precepts that's actually harder to accomplish than it might sound. When you're at work on something, use it as a touchstone. If you feel lost or confused, return to this question and make sure you're still writing that book that you want to read. I know that there might be days when whatever you've written feels like total drivel and you can't imagine that anyone would ever want to read it. I'm not talking about getting down on yourself or indulging your inner critic. I'm saying: don't write a book for the marketplace (vampire novels are in!) or because you want to sound like that super literary person in your workshop. You started writing because you love reading. You'll write your best book if you write the kind of book that you most love. Think about the qualities that go into your most beloved books, and try to pour that same energy into your own writing, to channel those same qualities. With practice, and in revisions, it gets easier to get closer to this goal, I think. Other advice? Read four times as much as you write. That was the advice of a writing teacher of mine. It's hyperbolic, but the point is, you should write because you love to read, and you should read a lot and closely, because books (novels, not how to books) are the best teacher out there. Also: keep a journal of images and observations. You don't need to "diary," per se, but I do think it's good to have a place where you jot things down before forgetting them. It trains you to think with your eyes and your words at once.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed